In addition to his classics of horror fiction, it is estimated that Lovecraft wrote 100,000 letters — or roughly 15 every day of his adult life — ranging from one-page diaries to seventy-page diatribes. Perhaps 20,000 of those letters have survived, in the hands of private collectors and at the John Hay Library in Providence.

In each episode of this podcast, we'll read one of these letters (or part of it) and then discuss it. In his letters HPL reveals an amazing breadth of knowledge of philosophy, science, history, literature, art and many other subjects, and forcefully asserts some highly considered opinions (some of which can be upsetting).

And of course his letters offer a fascinating window into his personal life and times. Although we've been working with Lovecraftian material for over 30 years, we still find interesting new things in his letters, and while we don't claim to be experts we look forward to sharing them with a wider audience.

Subscribe via iTunes, Stitcher or wherever you get podcasts! Or listen right here!

RSS Feed- Episode 32

- Posted May 31, 2020

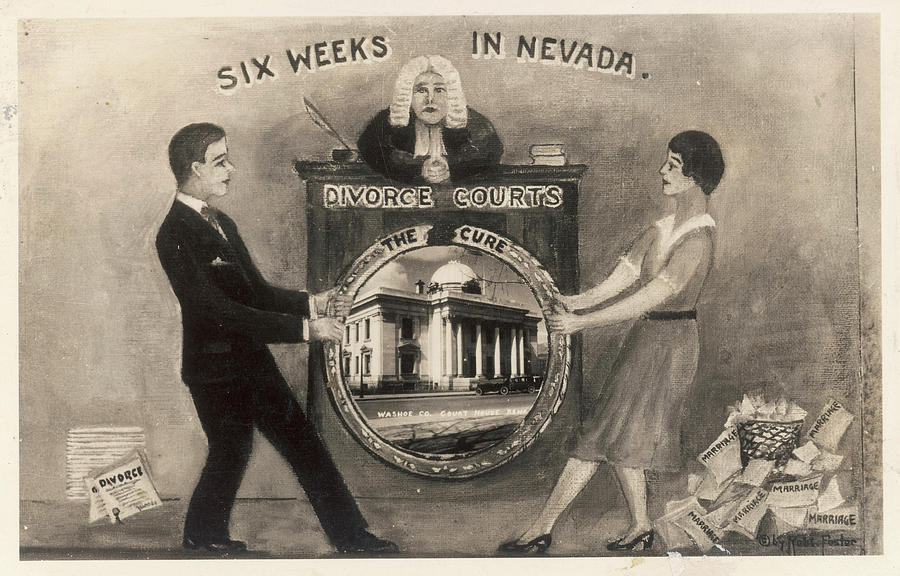

Divorce and Bigamy

In this letter of July 2, 1929 to Maurice Moe, HPL discusses his thoughts on marriage and, more importantly, divorce. Written after the collapse of his own marriage, Lovecraft is quite candid about the institution and his personal life.

Our thanks again to our friends at Hippocampus Press for their book Letters to Maurice Moe and Others.

Lovecraft has never been famous for the brevity of his style, but even for him the opening sentence of this letter seems long, weighing in at 164 words.

HPL mentions Judge Benjamin Lindsey in this letter, who co-authored The Companionate Marriage with Wainright Evans in 1927.

SLANG ALERT: HPL uses the word "flivvers" in this letter. The ubiquitous automobile of the 1920s was the Ford Model T, often referred to as a "flivver", but the word in general means "failure".

HPL mentions "flaming youth", a phrase which alludes to the shocking novel of 1923 and/or the notorious film adaptation of it. The novel was written by Samuel Hopkins Adams, but published under the pseudonym "Warner Fabian" to protect his reputation. You can read Flaming Youth here. Only one reel of the film version survives, kept in the Library of Congress.