In addition to his classics of horror fiction, it is estimated that Lovecraft wrote 100,000 letters — or roughly 15 every day of his adult life — ranging from one-page diaries to seventy-page diatribes. Perhaps 20,000 of those letters have survived, in the hands of private collectors and at the John Hay Library in Providence.

In each episode of this podcast, we'll read one of these letters (or part of it) and then discuss it. In his letters HPL reveals an amazing breadth of knowledge of philosophy, science, history, literature, art and many other subjects, and forcefully asserts some highly considered opinions (some of which can be upsetting).

And of course his letters offer a fascinating window into his personal life and times. Although we've been working with Lovecraftian material for over 30 years, we still find interesting new things in his letters, and while we don't claim to be experts we look forward to sharing them with a wider audience.

Subscribe via iTunes, Stitcher or wherever you get podcasts! Or listen right here!

RSS Feed- Episode 60

- Posted May 2, 2021

Four for Farnsworth

A set of four letters to Weird Tales editor Farnsworth Wright, spanning from July of 1927 to July of 1936. Over a nine year period, we see the evolution of their relationship and delve into topics including the submission of "The Call of Cthulhu", a mystery tale by Zealia Bishop, and the untimely death of Robert E. Howard. We try to get to the bottom of the "black magic" quote and find there's no bottom to the copyright question.

Music by Troy Sterling Nies. Transcript by Olivier Decker. Thanks again to Hippocampus Press for their book The Lovecraft Annual #8, which includes all of these letters to Farnsworth Wright. Thanks to Cryptic Publications for Crypt of Cthulhu Vol. 6, Num. 6, 1987, which includes David E. Schultz's essay about the "black magic quote". Thanks also to Arkham House for Lovecraft Remembered, edited by Peter H. Cannon, which includes Donald Wandrei's memoir of HPL. If you want to read more letters to Zealia Bishop, you can check out our very own book, The Spirit of Revision.

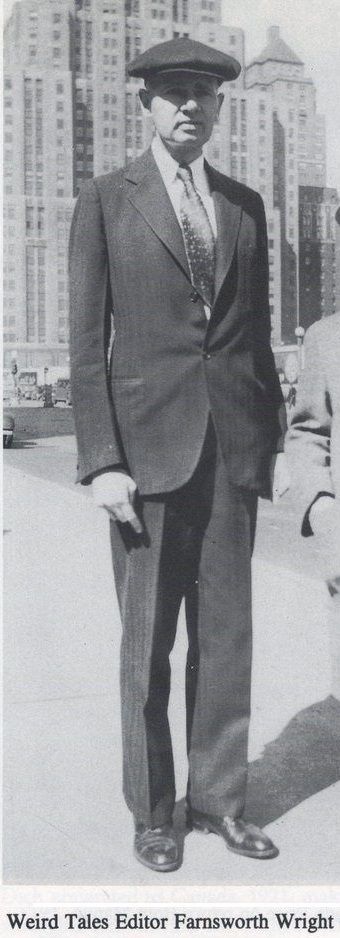

Here's Wright posing on what appears to be Michigan Avenue in Chicago, with the iconic Palmolive Building in the background, not far from the Weird Tales offices. He was described as a tall, thin man with a small voice who seemed prematurely aged (he was barely two years older than Lovecraft). That might be due in part to the traumas he suffered in his youth, including the death by drowning of his college roommate and being drafted as an infantryman in WWI.

Here's Wright posing on what appears to be Michigan Avenue in Chicago, with the iconic Palmolive Building in the background, not far from the Weird Tales offices. He was described as a tall, thin man with a small voice who seemed prematurely aged (he was barely two years older than Lovecraft). That might be due in part to the traumas he suffered in his youth, including the death by drowning of his college roommate and being drafted as an infantryman in WWI.

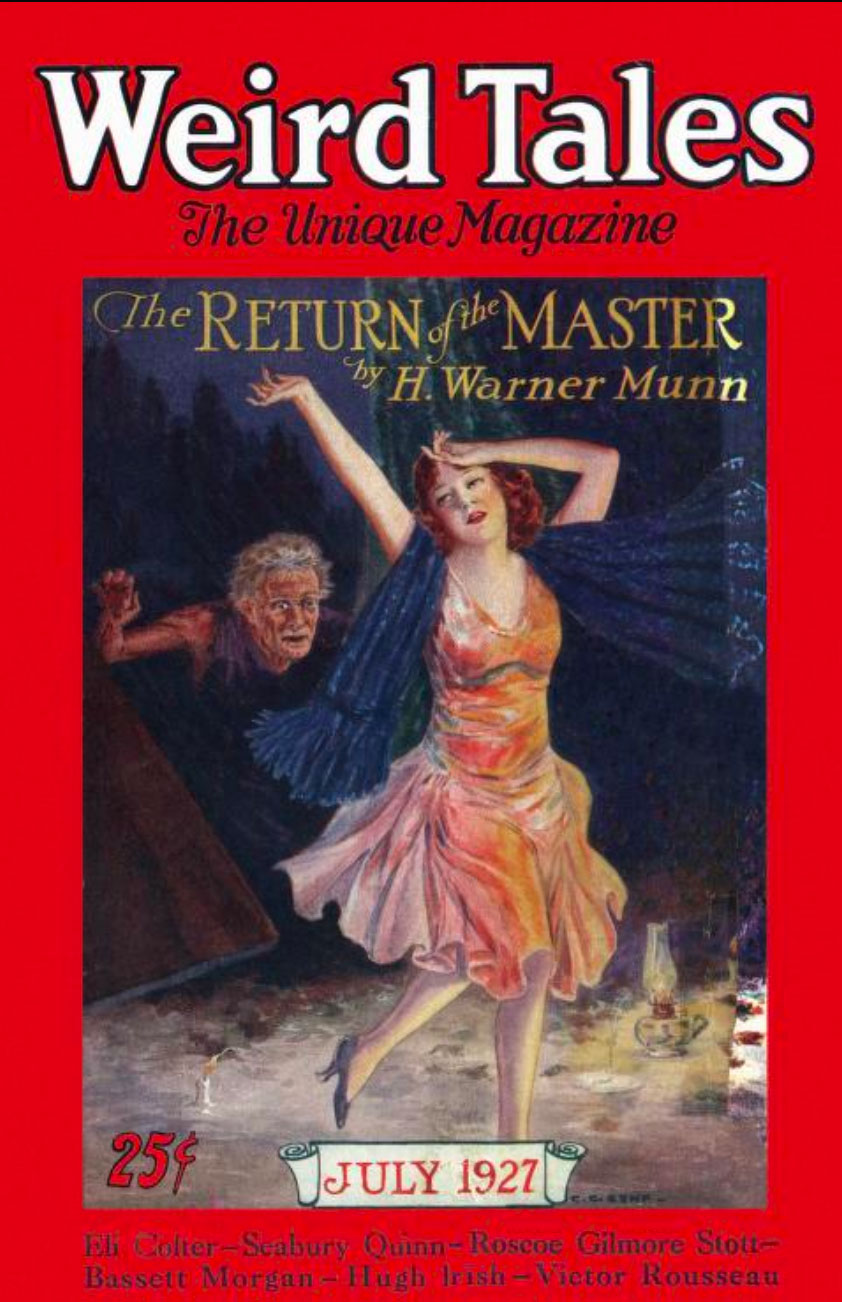

Although HPL did pile considerable scorn on the readers of Weird Tales, he did have some praise for a couple of items in the issue that came out the month he wrote this first letter. Click on the link to read "The Mystery of Sylmare" by Hugh Irish, and at the same time see a drawing by Hugh Rankin, the new illustrator HPL liked. Rankin would make drawings for a number of HPL's appearances in the magazine, including "The Call of Cthulhu", "The Dunwich Horror", "The Silver Key", "Pickman's Model", "The Curse of Yig" and "The Lurking Fear".

Although HPL did pile considerable scorn on the readers of Weird Tales, he did have some praise for a couple of items in the issue that came out the month he wrote this first letter. Click on the link to read "The Mystery of Sylmare" by Hugh Irish, and at the same time see a drawing by Hugh Rankin, the new illustrator HPL liked. Rankin would make drawings for a number of HPL's appearances in the magazine, including "The Call of Cthulhu", "The Dunwich Horror", "The Silver Key", "Pickman's Model", "The Curse of Yig" and "The Lurking Fear".

In the second letter, HPL asks when "The Curse of Yig" might appear. It was not published for another 14 months, in the issue for November of 1929, but Zealia's name made the cover, and she was in good company: the issue also featured pieces by Clark Ashton Smith, Robert E. Howard, August Derleth, Seabury Quinn and David H. Keller.

Here's the postcard that Donald Wandrei sent to Lovecraft after his first day in Chicago. We can only hope actually meeting Farnsworth Wright at the Weird Tales offices improved his opinion of the city, which, for the record, is wonderful. Wright infamously rejected some notable HPL stories, including "The Shunned House", "The Call of Cthulhu" (too obscure), "At the Mountains of Madness" (too long), "In the Vault" and "Cool Air" (too gruesome), and "The Shadow Over Innsmouth" (rejected twice!).

Here's the postcard that Donald Wandrei sent to Lovecraft after his first day in Chicago. We can only hope actually meeting Farnsworth Wright at the Weird Tales offices improved his opinion of the city, which, for the record, is wonderful. Wright infamously rejected some notable HPL stories, including "The Shunned House", "The Call of Cthulhu" (too obscure), "At the Mountains of Madness" (too long), "In the Vault" and "Cool Air" (too gruesome), and "The Shadow Over Innsmouth" (rejected twice!).

HPL mentions a number of "horror" movies that greatly disappointed him in the third letter. Frankenstein and Dracula are pretty famous films from 1931, but you might not have seen The Bat, made in 1926. Based on a hit stage play, which was itself based on a popular novel, The Bat was intended as a comedy/mystery, so HPL's criticism that it wasn't sufficiently "horrible" might be a little unfair. Directed by Roland West, the movie opens with what might be one of cinema's first "spoiler alerts". Because it was based on hit properties, they made a number of changes to the plot so that people who had already seen the play or read the book could enjoy the movie as something new. It featured a number of people on the crew who would go on to be heavy hitters in Hollywood, including cinematographer Gregg Toland and production designer William Cameron Menzies. The movie was itself a hit, and Roland West remade it as The Bat Whispers in 1930, this time as a talkie. This was also a very influential film, being one of the first productions to use widescreen technology that wouldn't be attempted again until the 1950s, and made extensive use of miniatures and models. We don't know if HPL watched that version, but Bob Kane did, and was still thinking about it in 1939 when he created Batman. That movie was itself remade in 1959, once again titled The Bat, but this time starring Vincent Price and Agnes Moorehead. All three versions of the movie are watchable online, and you can see the first two below!

All these movies were ultimately based on the novel The Circular Staircase by Mary Roberts Rinehart, who has been called "the American Agatha Christie" and apparently invented the mystery trope of "the butler did it". She was quite happy to see her work adapted into film, which happened numerous times. Lovecraft did not want "The Dreams in the Witch House" to be adapted into a radio show, but it has been done not only in that format but also as a stage play by Chicago's WildClaw Theatre, as a movie by Stuart Gordon, and as a rock opera we happen to like! Furthermore, Roald Dahl's 1983 novel The Witches features a character named "Bruno Jenkins". Since "Bruno" is derived from an old German word for "brown" and the boy gets turned into a mouse, it would seem that character is a wink to HPL's story. HPL probably wouldn't have liked any of these things.

Chris J. Karr has explored the question of Lovecraft's copyright status in depth, and he has published the results of that study at The Black Seas of Copyright.

The two manuscripts HPL casually included with the fourth letter, presuming (or maybe pretending?) they would be rejected, were "The Haunter of the Dark" and "The Thing on the Doorstep". Wright accepted both of them and they were published in December of 1936 and January of 1937, respectively. The disastrous financial flop of The Moon Terror doomed any further attempt Wright might have made to publish anthologies, but some of HPL's stories did appear in the "Not At Night" series published in the U.K. by Selwyn & Blount.

The two manuscripts HPL casually included with the fourth letter, presuming (or maybe pretending?) they would be rejected, were "The Haunter of the Dark" and "The Thing on the Doorstep". Wright accepted both of them and they were published in December of 1936 and January of 1937, respectively. The disastrous financial flop of The Moon Terror doomed any further attempt Wright might have made to publish anthologies, but some of HPL's stories did appear in the "Not At Night" series published in the U.K. by Selwyn & Blount.

HPL clung to hope that the news of Robert E. Howard's suicide was somehow wrong. He had not seen this clipping from the June 14, 1936 issue of the Abilene Morning Reporter-News with details of the double funeral of REH and his mother.