In addition to his classics of horror fiction, it is estimated that Lovecraft wrote 100,000 letters — or roughly 15 every day of his adult life — ranging from one-page diaries to seventy-page diatribes. Perhaps 20,000 of those letters have survived, in the hands of private collectors and at the John Hay Library in Providence.

In each episode of this podcast, we'll read one of these letters (or part of it) and then discuss it. In his letters HPL reveals an amazing breadth of knowledge of philosophy, science, history, literature, art and many other subjects, and forcefully asserts some highly considered opinions (some of which can be upsetting).

And of course his letters offer a fascinating window into his personal life and times. Although we've been working with Lovecraftian material for over 30 years, we still find interesting new things in his letters, and while we don't claim to be experts we look forward to sharing them with a wider audience.

Subscribe via iTunes, Stitcher or wherever you get podcasts! Or listen right here!

RSS Feed- Episode 37

- Posted July 5, 2020

Laundry and Influenza

Written during his time in New York, this richly detailed letter to HPL's Aunt Lillian discusses quotidian issues like laundry, and more impactful issues like the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918.

Music by Troy Sterling Nies. A special thanks this week to Donovan Loucks, for pointing this letter out and for his work to find the Peck Garden, and to David E. Schultz for making the letter available for us to read.

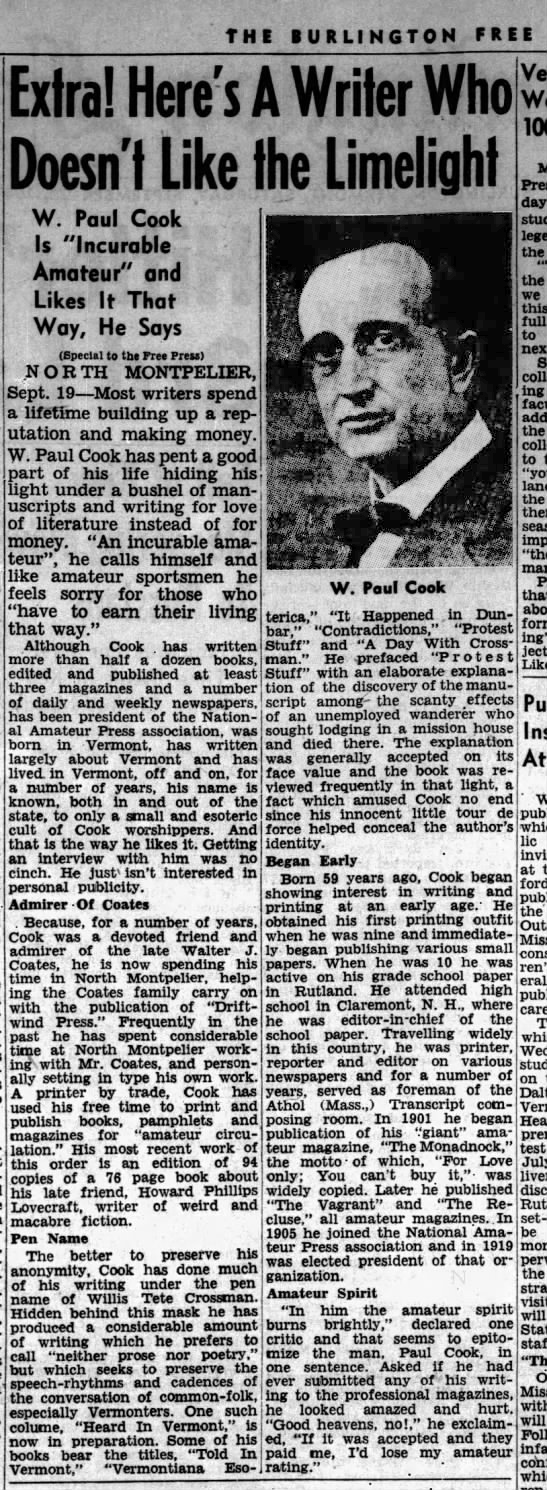

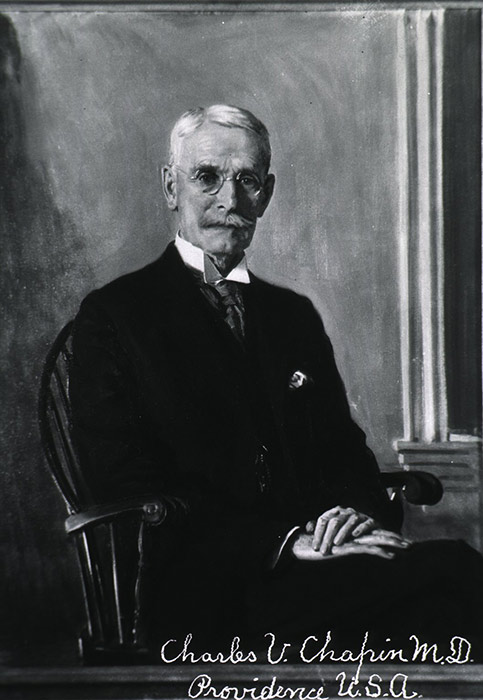

We found this clipping from the Burlington Free Press of September 20, 1941 about W. Paul Cook. And at right is a portrait of Providence public health titan Dr. Charles Value Chapin.

We found this clipping from the Burlington Free Press of September 20, 1941 about W. Paul Cook. And at right is a portrait of Providence public health titan Dr. Charles Value Chapin.

You can check out the archive of old Providence restaurant ephemera that Sean found here!

This letter is absolutely loaded with specific but glancing references and we couldn't talk about all of them in the episode. HPL refers to the price difference between coke and bituminous coal, which reminds us that in his day most American homes were heated by burning coal of some kind in a furnace. Coke is a kind of refined fuel made from coal that was once popular. It's better and safer than straight bituminous coal, and therefore more expensive, but producing it was poisonously devastating to the environment around coking facilities. Today fewer than 130,000 homes nationwide are heated with coal.

HPL refers to his friend Everett McNeil's book Tonty of the Iron Hand. The title character is based on a real person, Henri de Tonti.

HPL mentions the "Pemaquid idea". We don't know exactly what he's talking about, but he may have been referring to the Pemaquid Point Light, a lovely lighthouse in Maine.

HPL confessed to ignorance of the Rowan tree legends. You need not be ignorant if you click here!

HPL also talks about "Laswell's Corners & Characters". This was a column that ran in the Providence Journal and Evening Bulletin in the 1920s, with drawings by staff artist George D. Laswell. Items were collected and published as a book in 1924, and it's loaded with lovely ink drawings of Providence architecture which HPL must have greatly enjoyed. You can see it online at the Internet Archive.

HPL mentions the "Peck Garden" which is next door to "Hathaway and Douglass". The garden was apparently the yard of a private home. His Aunt Lillian was staying at a boarding house in Waterman St., and must have discovered that the view from her window looked out over the neighbor's beautiful garden. Our friend Donovan Loucks is an expert on Lovecraftian sites in Providence, and with some amazing detective work he found the very location!

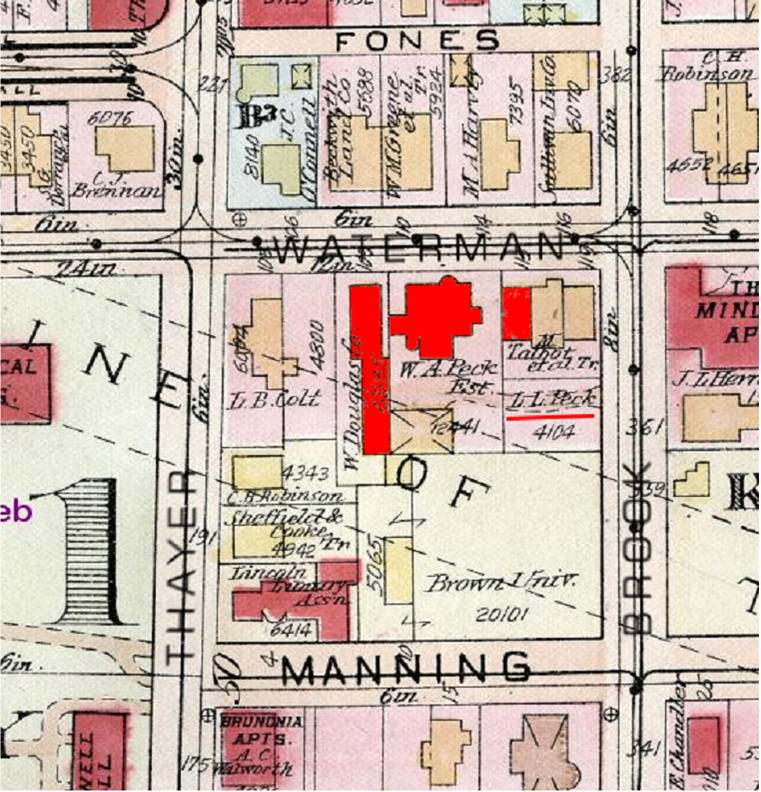

Donovan writes: "I've highlighted (in red) three buildings on the 1918 plat map seen at right: from right to left they are 115 Waterman Street, 113 Waterman Street, and 109 Waterman Street. 115 is the boarding house at which Lillian was staying, 113 is identified on the map as the home of "W. A. Peck" (which must be the site of the "Peck garden"), and 109 is shown on the map as "W. Douglas Co.". Armed with these addresses, I returned to the house directories. (Note that I only have house directories from 1895 to 1936.)

Donovan writes: "I've highlighted (in red) three buildings on the 1918 plat map seen at right: from right to left they are 115 Waterman Street, 113 Waterman Street, and 109 Waterman Street. 115 is the boarding house at which Lillian was staying, 113 is identified on the map as the home of "W. A. Peck" (which must be the site of the "Peck garden"), and 109 is shown on the map as "W. Douglas Co.". Armed with these addresses, I returned to the house directories. (Note that I only have house directories from 1895 to 1936.)

The house at 115 Waterman Street where Lillian stayed seems to have been a boarding house beginning around 1917 and all the way through 1936. It appears to have been a private home prior to that. At no point is Lillian listed among the residents. It’s likely that she only lived at this location for a few months.

The home at 113 Waterman Street was that of Walter A. and Louise L. Peck. The 1895 and 1903 directories just list Mr. Peck, the 1896 through 1901 directories list both Mr. and Mrs. Peck, and the 1905 to 1934 directories list Mrs. Peck only. These folks were probably Walter Asa Peck and Louisa (not Louise) Lyman Aborn Peck, who are both buried in Swan Point Cemetery. The only directory that indicates Mr. Peck’s occupation is the 1895 which merely says “wool”.

Note that on the map above I’ve also underlined what looks like the “L. L. Peck” property on Brook Street. I didn’t turn up anything in the house directories along that stretch of Brook Street between Waterman and Manning Streets, as if the lot was empty for decades. However, the map seems to show a driveway through this property to what may be a carriage house at the rear of the W. A. Peck property. It’s possible that a portion of the “Peck garden” was on this property as well.

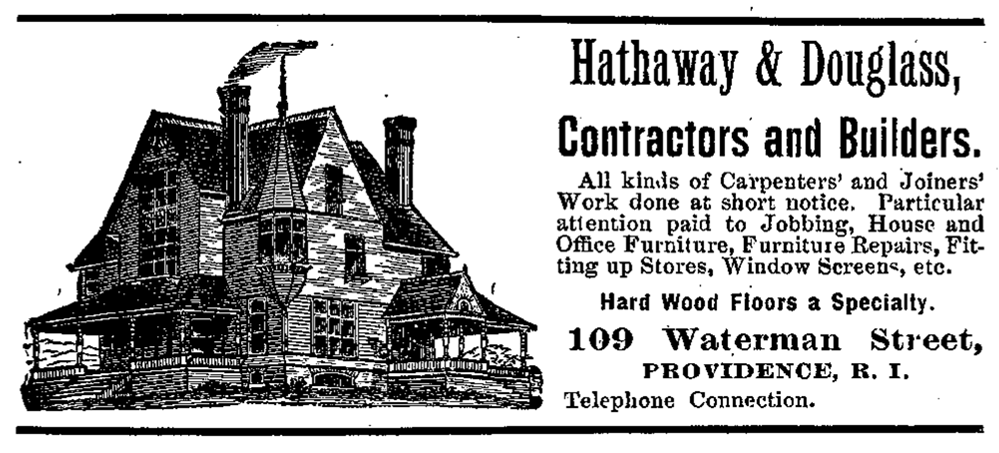

Finally, the building at 109 Waterman Street is listed as William Douglas & Co., Contractors in the 1921 through 1934 directories. But there’s no mention of a “Hathaway”. Going back further, the company is listed as William Douglas & Co., Carpenters from 1920 back to 1905. Then the company name changes to William Douglass & Co., Carpenters in the 1903 and 1901 directories. Finally, Hathaway & Douglass, Carpenters appears in the 1900 directory, going all the way back to the 1895 directory. At left is their advertisement from the 1897 directory."

Finally, the building at 109 Waterman Street is listed as William Douglas & Co., Contractors in the 1921 through 1934 directories. But there’s no mention of a “Hathaway”. Going back further, the company is listed as William Douglas & Co., Carpenters from 1920 back to 1905. Then the company name changes to William Douglass & Co., Carpenters in the 1903 and 1901 directories. Finally, Hathaway & Douglass, Carpenters appears in the 1900 directory, going all the way back to the 1895 directory. At left is their advertisement from the 1897 directory."

Donovan concludes: "Unfortunately, this entire area has been wiped clean and is now the site of the Brown University Sciences Library and Department of Computer Science."

In the postscripts to this letter, HPL asks his aunt if she can pick up a new calendar for 1926. We don't know if she did, but HPL's calendars from 1925 and 1927 are brilliantly preserved in the Brown Digital Repository.