In addition to his classics of horror fiction, it is estimated that Lovecraft wrote 100,000 letters — or roughly 15 every day of his adult life — ranging from one-page diaries to seventy-page diatribes. Perhaps 20,000 of those letters have survived, in the hands of private collectors and at the John Hay Library in Providence.

In each episode of this podcast, we'll read one of these letters (or part of it) and then discuss it. In his letters HPL reveals an amazing breadth of knowledge of philosophy, science, history, literature, art and many other subjects, and forcefully asserts some highly considered opinions (some of which can be upsetting).

And of course his letters offer a fascinating window into his personal life and times. Although we've been working with Lovecraftian material for over 30 years, we still find interesting new things in his letters, and while we don't claim to be experts we look forward to sharing them with a wider audience.

Subscribe via iTunes, Stitcher or wherever you get podcasts! Or listen right here!

RSS Feed- Episode 54

- Posted November 1, 2020

Whoop! Bang! Hooray!

In this exuberant letter to his aunt Lillian from March 27, 1926, HPL reacts to her recent suggestion that he come back home to Providence after his miserable years in New York City, and along the way talks about Freud, M.R. James, abiogenesis, Italian food, the high price of laundry, and a great many other things.

Music by Troy Sterling Nies. Thanks to Hippocampus Press for their book H.P. Lovecraft: Letters to Family and Family Friends. This letter comes from volume 2 of that excellent set.

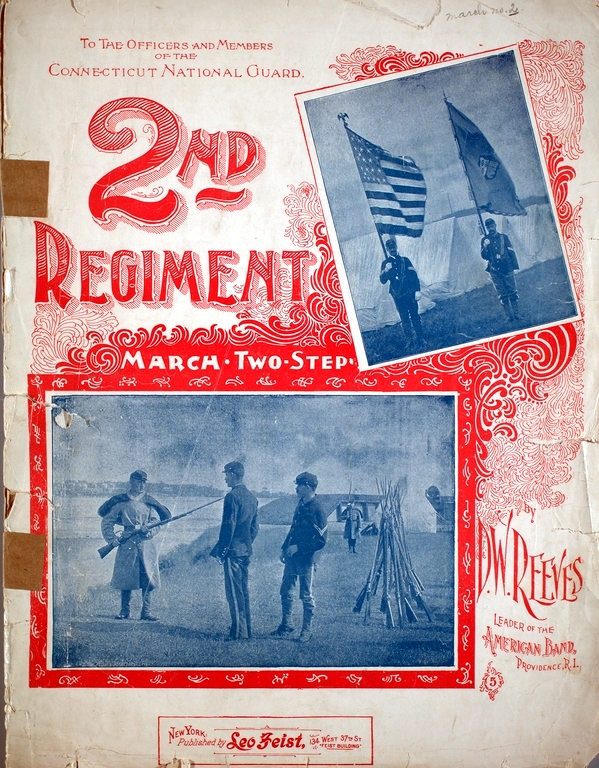

HPL apparently really enjoyed the military band music of his youth, and was very glad to know that Providence was erecting a monument to David Wallis Reeves, the "father of American band music". You can hear one of Reeves' most popular marches played by Lovecraft's favorite band at America's Juke Box from the Library of Congress. The American Band still exists in Providence, and the HPLHS' own Reber Clark has played with them and conducted them, and they have played Reber's music!

HPL apparently really enjoyed the military band music of his youth, and was very glad to know that Providence was erecting a monument to David Wallis Reeves, the "father of American band music". You can hear one of Reeves' most popular marches played by Lovecraft's favorite band at America's Juke Box from the Library of Congress. The American Band still exists in Providence, and the HPLHS' own Reber Clark has played with them and conducted them, and they have played Reber's music!

After gorging himself on a celebratory seven-course Italian meal, HPL took himself to see this movie. It is one of the westerns that made John Ford into a superstar director of American cinema.

Although we couldn't find the specific Mazur abiogenesis experiments that HPL refers to in this letter, we did learn about some other fascinating Herbert West types who were working at the same time. Alexander Oparin was a Russian biochemist who wrote The Origin of Life in 1924 and introduced the idea of the "primordial soup". In 1926, Hermann Muller discovered that x-rays can mutate genes, often with drastic results.

- Update

- Posted November 8, 2020

Fernando King and John F. Mazur

We're going monthly, so no new episode this week, but we do have a fascinating update about a couple of the people mentioned in last week's letter thanks to indefatigable researcher Dan Pratt!

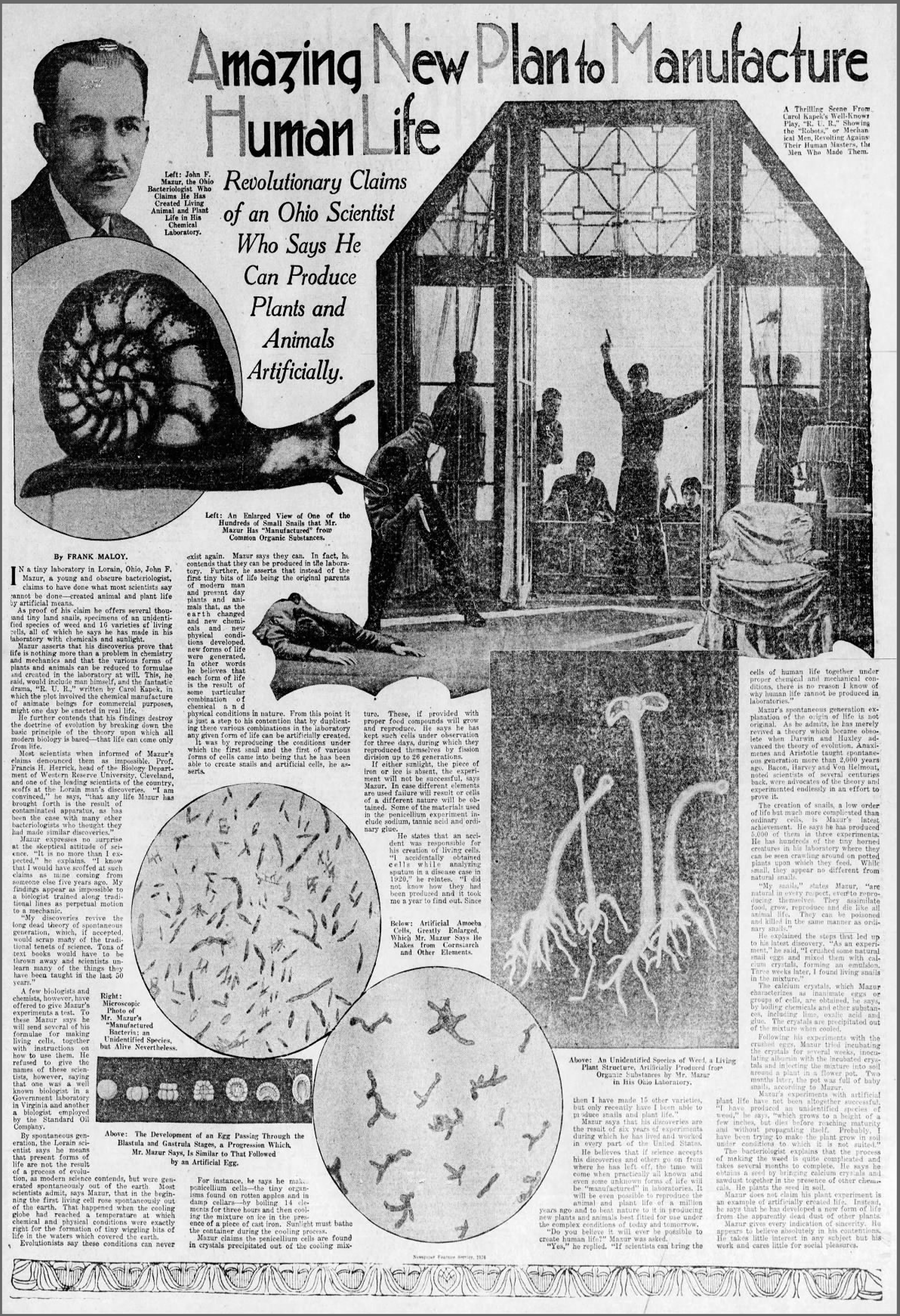

Dan scoured online newspaper archives and found a number of items about John F. Mazur, whose extravagant claims about creating artificial life in his laboratory got a fair amount of press coverage in the spring of 1926. Here is a big feature article from the June 6 issue of The Times of Shreveport, Louisiana. This clipping postdates HPL's letter so it can't be the one Aunt Lillian sent him, but syndicated stories about Mazur were being published from time to time that spring and no doubt something similar appeared in the Providence papers. Also shown below is a clipping from the March 26th Eau Claire Leader-Telegram.

Dan scoured online newspaper archives and found a number of items about John F. Mazur, whose extravagant claims about creating artificial life in his laboratory got a fair amount of press coverage in the spring of 1926. Here is a big feature article from the June 6 issue of The Times of Shreveport, Louisiana. This clipping postdates HPL's letter so it can't be the one Aunt Lillian sent him, but syndicated stories about Mazur were being published from time to time that spring and no doubt something similar appeared in the Providence papers. Also shown below is a clipping from the March 26th Eau Claire Leader-Telegram.

Dan writes: "Mazur may have seen an ad in Popular Mechanics in the late 1910s for the American College of Bacteriology, a possibly-fictitious institution that offered correspondence courses in public health, bacteriology, and sanitation (even offering a 3-month nursing degree—yikes). I say Popular Mechanics because he later advertised his own services there: "CHEMICAL and bacteriological examinations guaranteed accurate. Formulas, processes. Write me about your chemical problems. List free. J F Mazur M.B., 937 W 20th St. Lorain, Ohio" (March 1923).

Mazur apparently made his living by processing biological samples for physicians in his private lab, but used his spare time to try to manufacture life from basic chemical components. He was embarrassingly convinced that he'd created cells, yeast—finally, even snails. He also had an odd religious angle on his process, which didn't help the newspapers (or other reputable scientists) take him seriously.

Mazur apparently made his living by processing biological samples for physicians in his private lab, but used his spare time to try to manufacture life from basic chemical components. He was embarrassingly convinced that he'd created cells, yeast—finally, even snails. He also had an odd religious angle on his process, which didn't help the newspapers (or other reputable scientists) take him seriously.

The poor guy was undoubtedly a little mentally ill and it seems like the scientists asked to comment on his work were relatively kind. Less kind was the San Francisco Examiner (Sep 19, 1926): "It took Frankenstein, of fiction, five years to create his monster. Mazur has been working for six years, and all he has been able to do is create, by means of chemical formula and mixtures, artificial snails." Damn. Some people are never satisfied. (Props to the reporter, though, for providing the complete synopsis of Frankenstein.)"

Dan also found out pretty much the entire life story of Fernando King, HPL's barber, by searching census records, Providence city directories, and other archives. Born in 1858 and working in a mill by the age of eleven, King went through a few jobs before becoming a barber.

Dan also found out pretty much the entire life story of Fernando King, HPL's barber, by searching census records, Providence city directories, and other archives. Born in 1858 and working in a mill by the age of eleven, King went through a few jobs before becoming a barber.

Dan writes: "The first listing for the King & Fountaine salon appears in the 1895 City Directory: Room 112 at 72 Westminster Street (site of the present Turk’s Head Building, constructed 1913). Fernando’s business partner was Eduard Fountaine (a.k.a. Edward Fontaine) (b. 1864), a French Canadian who emigrated to the US in 1875." They changed locations and even split up over the years.

King lived to the age of 78, and passed away just one month before HPL himself did in 1937. He is buried in North Scituate, Mass. CLICK HERE to download a PDF full of more detail, including numerous photos of the places where King lived and worked.