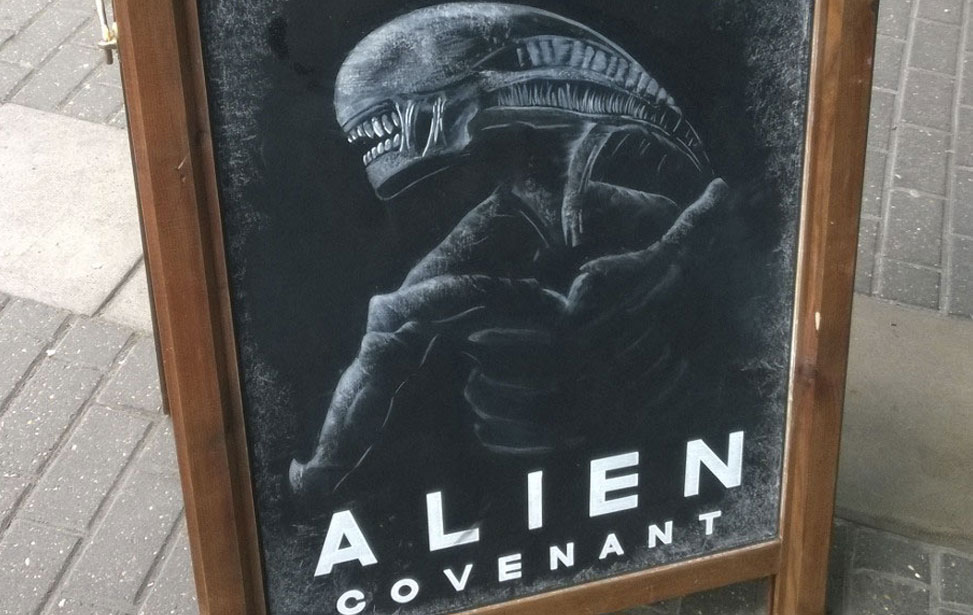

Alien: Covenant

Fast-paced, terrifying and exploring new and fascinating ideas, Alien: Covenant is a great contribution to the franchise. If it doesn't quite manage the sublime brilliance of the original Alien and is a little muddled in places, it is, as a stand-alone, still a good movie and well worth your time. BE WARNED: the trailer embedded here gives away too much. Just go see the movie!

- Overall: B B B b B

- Quality: Q Q Q Q Q

- Value: V V V V V

- Distributed by Twentieth Century Fox. Directed by Ridley Scott.

- In theaters May 19.

Review by William Dean

May 17, 2017

It is impossible to properly discuss Alien: Covenant without referring to its predecessors in the franchise. Ergo be aware that the following review will then inevitably contain spoilers for Alien (1979) and Prometheus (2012) – the reviewer will however refrain from revealing significant details about Alien: Covenant itself.

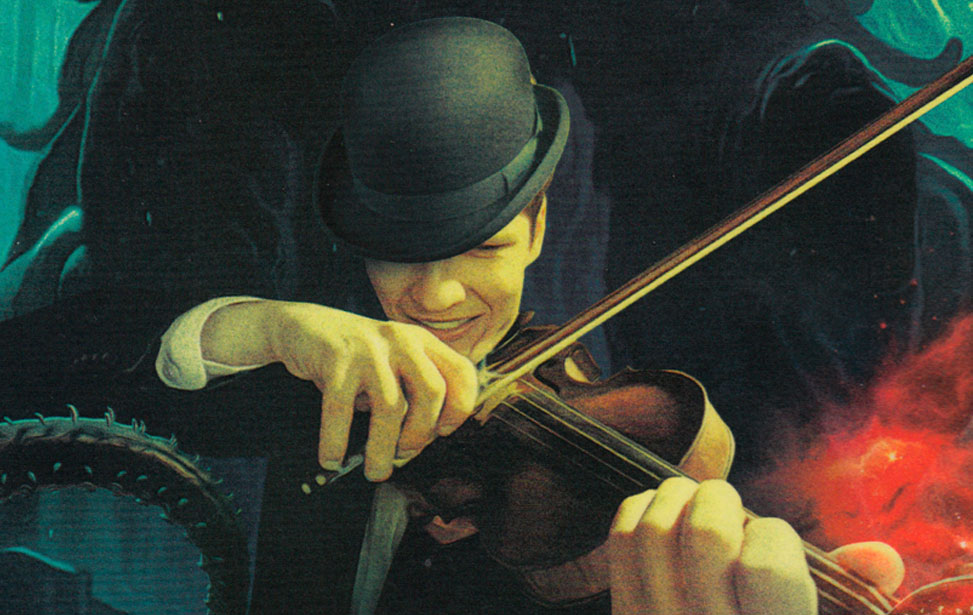

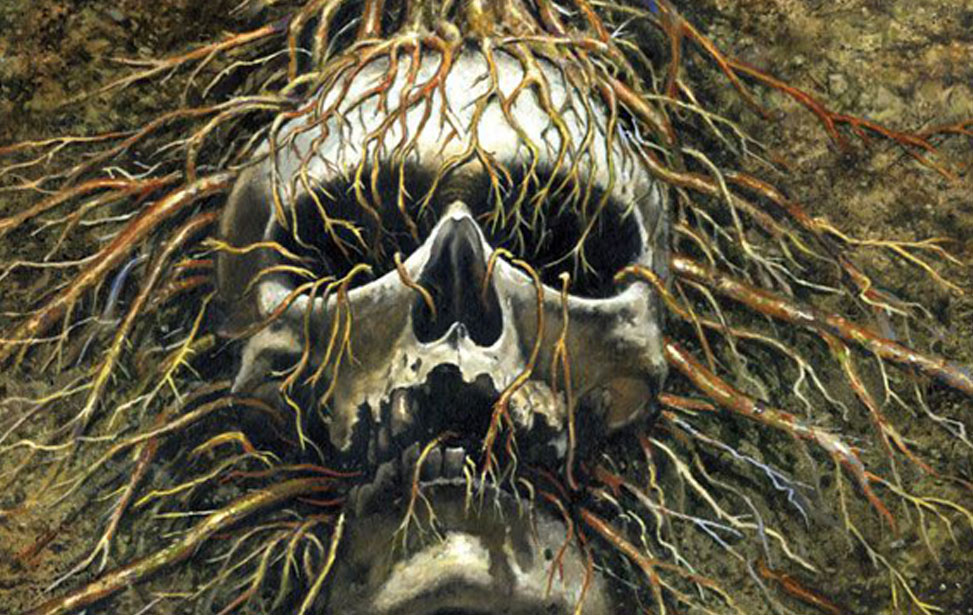

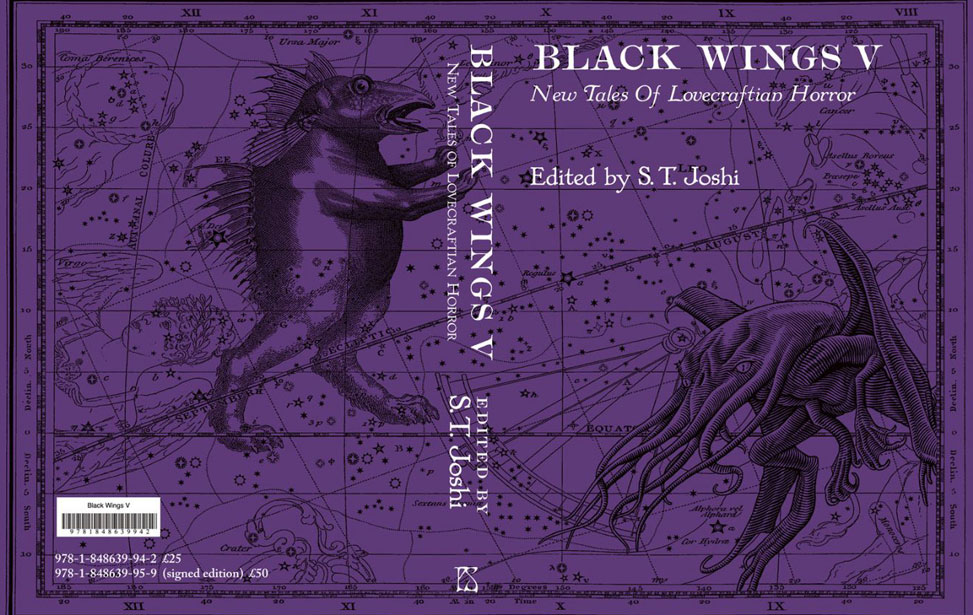

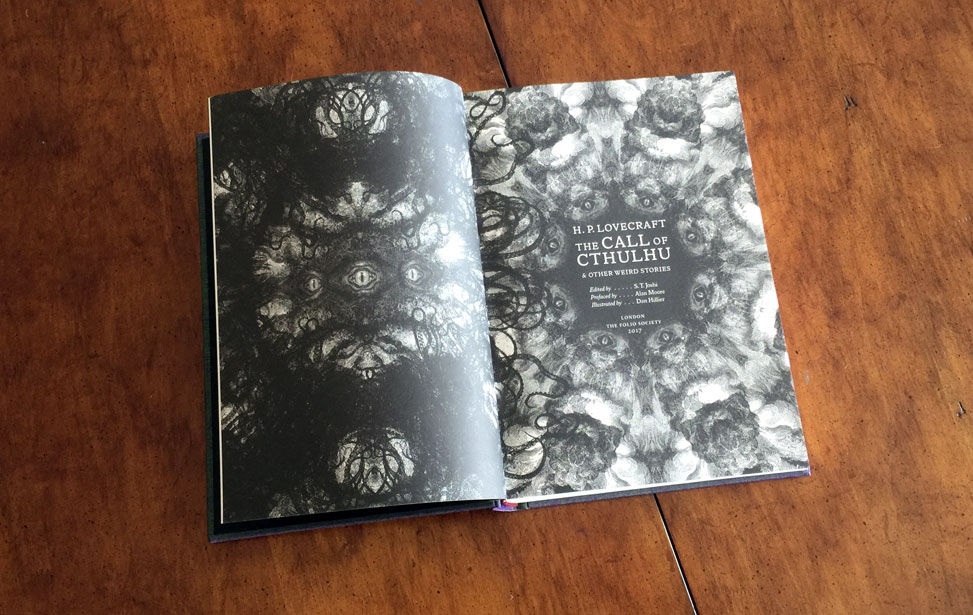

One likes to imagine that Lovecraft could only have approved of Ridley Scott’s 1979 movie Alien. It is that rare movie that perfectly balances mood, theme, and pace but also conveys concisely and articulately its message: that which lies beyond our tiny sphere of knowledge is terrifying; to seek too far is to eventually find nightmares that will destroy us. This very same idea is key to much of Lovecraft’s fiction-writing and personal philosophy – but one imagines he would also have admired Alien’s method. Amongst its stand-out components we can point to the claustrophobic sets, Alan Goldsmith’s brilliantly unsettling score, Giger’s hideous designs and of course the terrified performances of its cast. Collectively these elements pluck at some of humanity’s primal fears and successfully induce a deep sense of unease in the audience that has rarely been equalled, before or since, in the medium of cinema. It is a superb example of unity-of-effect in storytelling. As a stand-alone movie Alien is flawless.

It is not then until 2012’s Alien prequel Prometheus that we see the same themes revisited within the franchise. Aliens (1986), Alien 3 (1992) and Alien: Resurrection (1997) are all entertaining and effective in their own ways – but they have different aims, different messages and different ideas. Prometheus, however, harks back to that original concept found in Lovecraft’s writings, that should we venture outside our sheltered harbour of ignorance we may find that our new knowledge comes at too great a cost.

Recall: a crew of scientists and explorers follows a trail into space on the starship Prometheus, drawing on clues left by early man, hoping to find the truth of humanity’s origins. Full of hope and optimism at what they might learn, instead they discover that humanity was created, at best, as some sort of lesser and inferior species; at worst, we were bred by our creators – known as the Engineers – to be slaves, animals, food, fodder and raw material for their terrible technology. Humanity may even have been an accident. The message at the core of Lovecraft’s At the Mountains of Madness (1933) has rarely been displayed with such stark brutality. Humanity’s forerunners, on meeting their creations, turn out to be anything but kind and benevolent to their descendants: when the android David speaks to the awakened Engineer in its own language, stating magnate Peter Weyland’s belief that his [Weyland’s] faltering life can be extended by the Engineers, it flies into a rage and murders the party. We do not know exactly why, but we can make an educated guess. Perhaps David broke some cultural taboo; but more likely the Engineer’s reaction was simply the shock and anger of being addressed in one’s own tongue by, what was to it, the discarded afterbirth of an abandoned science-experiment. Before our protagonists manage to stop the Engineer we see it laying in a course to Earth – presumably to correct a mistake by eradicating the aberrative human race. The movie ends with Dr. Shaw and David, the only survivors, leaving the planet and seeking the Engineer’s homeworld in its own, intending to confront their creators on their own terms.

Conceptually the Prometheus movie is a direct successor to Alien. It takes that terrifyingly bleak cosmic reality and moves it one step further, twisting the notion of human-centric teleology – the idea that humanity is moving in a specific direction under the direction of a deity – quite wickedly. Something was directing humanity – but it wasn’t God.

So now we come to Alien: Covenant, the next film in the Alien series, direct sequel to Prometheus, and, if we’re honest, a movie with some big conceptual boots to fill and a lot of expectations to live up to. For the most part, it manages them.

Briefly overviewing its plot: a decade after the events of Prometheus the spaceship Covenant, laden with sleeping colonists and frozen human embryos, arrives over a seemingly perfect new world. With their cargo still safely in hibernation, Covenant’s crew descend to the planet’s surface to reconnoitre and evaluate their potential new home. It is difficult to say more without giving away pertinent details – but suffice to say that their paradise is not what it seems. The crew discover the legacy of Prometheus’s voyage and they must pay the price for what mankind has done. To say any more would be to ruin the opportunity for you to discover it for yourself. In fact if the reviewer had one piece of advice, it would be to avoid watching the trailer for the movie embedded above – even that shows too much!

Covenant works within the same concept of cosmic pessimism, but takes a different approach to Prometheus. It is worth considering the mythology associated with the latter: Prometheus was the man who stole fire from the Gods in order to warm humanity and engender civilisation. The Gods however were angry at his theft; Prometheus’ punishment for elevating humanity was to be chained helpless to a rock and to have his liver pecked out by birds for all eternity. This fits perfectly with the theme of the movie Prometheus – mankind reaches for fire, but must pay a terrible price.

Covenant, if we continue the Classical theme, is more about hubris: arrogance; defiance of the gods. Mankind have created subservient androids that are intellectually and physically superior to itself – this movie introduces the new android Walter (played with precision by Michael Fassbender) – and we are beginning to reach out, as a species, to new worlds. Humanity’s future looks bright, optimistic, safe and assured – but there is an arrogant insolence to our character. This is wonderfully illustrated in a flashback scene at the very beginning of a movie between the newly minted android David (also Fassbender) and a young Peter Weyland (played with perfect smugness by Guy Pearce). In Covenant it is this presumption that may prove our downfall. The price of hubris, in Classical mythology, is nemesis: the inescapable agent of inevitable vengeance.

It is also worth considering the original working title of Covenant: originally the movie was to be called Alien: Paradise Lost. A literal reading of the title “Paradise Lost” would have been a perfect fit for this movie; however many other parallels can be made between Milton’s epic poem and this movie: the innocence of Adam and Eve and their folly; the great tempter Satan – himself only a product of his creator. This latter idea in particular is a strong theme in the movie – the relationship between creator and creation: how can we ever be anything more than that for which we were made? In his dual role as the androids David and Walter, Fassbender portrays this dilemma wonderfully. So there is the relationship between humankind and android; but then also there comes the relationship between the Engineers and humankind. There are interesting parallels hinted at, that the Engineers as creators may have more in common with humanity than is first apparent. Although the concepts are never fully explored or fleshed out in Covenant they are clearly on the writers’ minds and the question is posed. As readers of Lovecraft we cannot help but think of At the Mountains of Madness – that moment when Professor Dyer makes the staggering realisation that the Elder Things, like the Engineers in the Alien franchise, were, in their own way, men.

It is worth acknowledging that technically the film is magnificent: beautifully shot with fabulous effects and superbly acted. It comes with all the right boxes ticked, and on most levels Covenant is a success. The look and aesthetics are very strong; the costumes and technology sit somewhere between the custom-fitted bleeding-edge gear seen on the high-profile mission on the prototype Prometheus and the mass-produced cheap functionality of the working space-hauler the Nostromo: it says something about where the movie sits within the franchise's timeline, and helps with a sense of continuity. Elements like this give the sense that the film is very-well thought-out and complete. It is, for the most part, a very good film. The pacing in particular is brilliant – although that should perhaps be qualified by saying that, for such a conceptual film, it could have benefited with taking its time over certain moments. This is not just for introspection and ideas, which help drive mood, but also sometimes to enhance action. The drawn-out death of Kane in Alien is one of the greatest moments in cinema; the entire movie is terror moving like molasses. Covenant could have stood to learn this lesson. And like Alien, Covenant has a fantastic ensemble cast; but unlike Alien, Covenant does not spend time enough with nearly any of them to significantly contribute to the plot.

It is also sadly worth mentioning there are also occasional moments of lazy scripting. While Covenant does not suffer from this as much as its immediate predecessor Prometheus, there are nevertheless some moments of rather questionable stupidity from the characters. These are of the so well-known and so frequently-lampooned type that the movie Cabin in the Woods tells a bemusing fantastic horror story explaining them away. The viewer finds themselves trying to find explanations for the characters’ behaviour as they occasionally act without any sense of self-preservation. Ultimately even if the viewer can come up with an explanation, their very presence distracts from the movie and suspends belief. They are especially unforgivable because they are for the most part easily fixable with very minor changes to script and dialogue.

The reviewer is aware that he has written almost as much about Prometheus in this review as he has about Covenant. This is because Covenant, packed with good ideas as it is, is sometimes a touch muddled and incoherent. In writing this review and thinking about the earlier movies in the franchise, however, Covenant immediately made much more sense. The movies work phenomenally well as a pair but individually — especially Covenant — they sadly do not feel entirely complete.

The reviewer must end with an acknowledgement that he is very demanding in his expectations of a Ridley Scott Alien movie. If the reader can excuse a brief moment of autobiography, the first three Alien movies were very much a part of the reviewer's childhood. He remembers school friends, with elder siblings happy to share videos and parents with more liberal and open ideas as to what a young child may watch on TV, telling stories about the Alien movies: the eggs, the face-huggers, the chest-busters, the barracuda-like inner-jaws of the aliens, the flame-throwers, the motion sensors, the terror. He read the novelisations by Alan Dean Foster around the age of ten, watched the movies as soon as his over-indulgent grandparents would let him, around the age of 11, and in his early teenage years read every bad Alien comic and novel he could get his hands on. He watched Alien every weekend for at least a year or so around the age of 12. He still finds that original movie terrifying. Eighteen months after buying Alien: Isolation he still finds the game too tense and frightening to play for more than very short periods (Ripley is still hiding in a locker somewhere in medbay looking for a surgery kit). It's safe to say he's a big fan: Alien means a great deal to him. So he has high expectations, and is demanding more from this movie than most.

Alien: Covenant isn't everything he had been waiting and hoping for. It's not perfect. But it's pretty damn good, and worth your money.