Black Dog Traditions of England

Folklore Tapes have created a multi-disciplinary art experience utilising a variety of mediums - book, DVD, art-prints and 12" LP - to explore the traditional English folk-legends surrounding ghostly Black Dogs. Aesthetically and intellectually scrumptious, fans of experimental music and traditional ghost stories will find this a rare treat.

- Overall: B B B B B

- Quality: Q Q Q Q Q

- Value: V V V V V

- Folklore Tapes. By Ian Humberstone, David Chatton Barker et al.

- Price: £58.00/$80.00

VISIT THE U.S. PRODUCT SITE

Review by William Dean

June 16, 2017

England is a country of legends and, being a Westcountry lad, I heard a great many of them growing up. I recall one in particular: a schoolyard story about a nearby Church graveyard where, if you walked around a particular mausoleum backwards three times at midnight and stuck your fingers in the railings, then – the Devil would bite your fingers off. It’s a classic folk story, and one I’ve since learned is associated with many Churches up and down the country. The first time I heard somebody attribute the legend to another Church I recall being offended: this was our local legend! The Devil was Cornish and we were, bizarrely, perversely proud that he’d want to devote his attentions to us. Possessiveness of the story did eventually fade however, and I began to wonder instead how the legend actually began, and where it began. Collecting these sorts of tales, tracing their origins and unravelling their meanings – this is the job of a folklorist.

Black Dog Traditions of England, the item under review here, is a fascinating project by folklorist-scholar-artists Ian Humberstone and David Chatton Barker of Folklore Tapes. As they describe themselves, Folklore Tapes are “an open-ended research project exploring the vernacular arcana of Great Britain and beyond; traversing the myths, mysteries, magic and strange phenomena of the old counties via abstracted musical reinterpretation and experimental visuals. The driving principle of the project is to bring the nation’s folk record to life, to rekindle interest in the treasure trove of traditional culture by finding new forms for its expression.” With Black Dogs Ian and David are investigating one of England’s most notorious pieces of folklore. Made internationally famous by Sir Athur Conan Doyle’s The Hound of the Baskervilles, his tale was inspired by a number of different Black Dog legends from all around England. This boxed set uses a number of mediums to examine these peculiar traditions.

The box itself is very nicely embossed with the shape of a Rorschach blot resembling a hound – entirely appropriate for the spectral and ambiguous nature of the phenomena explored within. Inside the lid is a very nice hand-stamped print, indicating its number from the limited edition. The box contains the following:

To begin with, the book: at approximately 70 pages it is an excellent briefing on the subject of Black Dog legends. I read the book in one sitting and came away with a much enhanced understanding of Black Dog traditions and their place in English society. This is not a book of ghost stories: predominantly written in a review style, the book is designed to inform and provide context about the legends rather than send a shiver down the spine of the reader. The writing is eminently accessible and penned in such a style that somebody with no background in folk-tales (such as myself) can easily read it. Interesting all by itself, the book also provides a number of insights into the concepts that inform the music of the LP. A curiosity I noted was that the writing style did seem to meander across the essays: occasionally, and outside of quotations from primary sources, it uses the flourishes and narrative style of a storyteller addressing an audience; at other times it takes a drier and more academic tone. Neither approach is ineffective — but the occasionally modifying style is peculiar.

Following an introduction to the mythology in general, the book discusses Black Dog traditions in eight specific locales around England. Each gets its own concise chapter, none being longer than a few pages of text, accompanied by a number of full-colour photographs – the book is best thought of as a collection of short annotated essays. Helpfully, the discussions are all properly referenced to a list of footnotes and academic sources in the rear of the book. I was most impressed with this – it displays a level of intellectual and academic rigour rarely found in projects made available to the layman.

It is the LP itself that is at the heart of the box-set. This is a 140g 12” black vinyl with paper inner and card outer sleeve. There are nine tracks split across its two sides, comprised of field-recordings, narrations and noise-art in various combinations. The album is best described as “experimental” and a number of different audio approaches are explored: ranging from straight treated ambient-noise tracks to eerie horror-movie themes, some with narrative voice-overs and others without. I shall discuss several of the tracks in detail in order to give an idea of what to expect from the album as a whole.

The LP opens with Black Dog Summons. The core of this track is a field-recording from remote Blythburgh Church in Suffolk, a location mentioned in the book as the site of three deaths at the hands of the Black Dog of Bungay and where burn marks on the Church door are a supposed legacy of the assault. The sounds are pure rural England – I grew up with them in my ears. Soon though these are joined by the noise of clock-gongs (played in studio). Reminiscent of church bells summoning the faithful for service at dusk, the gongs echo and rattle in a dissonant manner and distort the pleasant pastoral image: these bells are not calling for the faithful, but for something that lurks in the shadows. As the gongs begin to fade the track ends to the sound of irregular deep bass thumps, like the sound of heavy paws padding, inexorably, relentlessly, across the ground. This is a summoning of something hellish: the listener develops to disconcerting sensation that something unearthly has arrived. The overall effect of this opening is remarkably unsettling and technically very cleverly constructed. It takes familiar and comfortable sounds, replicating a scene of everyday village life, then, with a subtle perversion, turns that scene into one of impending doom. The listener finds him-or-herself placed into an isolated and vulnerable listening state. This track is just the opening – but you are now perfectly receptive for the chilling impressions of strange entities haunting England about to be delivered to your ears.

This sense of menace rarely lets up across the album. Track two, The Barguest of Dob Park Lodge, is treated noise-art played on tape-loops and invented and prepared instruments. Whereas the first track prepared you for horror, this second one reveals it to you fully with the distressing quivers, jangles and screams of saw frames, cymbals, domestic harps, and the cyclical wheel of a carillon. Humberstone and Barker, it must be said, are both very talented noise-artists. The music is both technically strong and very effective at communicating mood.

It’s not until track three, The Black Dog of Uplyme, that we hear a human voice. We listen to a quiet, unpresuming and almost apologetic west-country gentleman narrating the tales of Uplyme’s canine apparition. The ambient tones of a synthesiser and the chimes of a music box accompany the narrator and provide tone, but it is the narrator’s voice that undoubtedly leads the track: his slightly halting diction adds a degree of authenticity to the legend. The story itself, under different circumstances, might be considered nothing more than an academic curiosity for a folklorist – but, on-edge as we are, the tale nevertheless finds its mark; the idea of somebody vanishing in a country lane, enveloped and consumed by a shadow, chills to the bone rather than appearing a rustic superstition.

Across the album there are three narrations in total, each from a different local storyteller. These tracks can perhaps be considered the focuses of the record, giving it cohesion and theme. The other two, Tales of Black Shuck and The Black Dog of Newgate, are both more professionally narrated than the aforementioned Uplyme and are perhaps then more conventionally told, with appropriate pace and flourishing. They are each in their own way compelling. The remaining tracks continue to develop the field-recordings, noise and music, exploring different ways of unsettling the listener. The Procession at Black Dog Village, where locals would once parade to celebrate their Black Dog, has a charming touch of folk-whimsy to it, before ending with a vaguely ill-sounding bend that seems to threaten something darker behind the festival. The Legend of Black Vaughn, the only track that might conventionally be called “music”, is a theme that John Carpenter might have been proud of – made all the richer by Humberstone’s prepared instruments dancing across it. The trickle of water, dissonant plinking and peculiar trilling warbles on The Barguest of Troller’s Gill puts the listener in mind of the wild fairy grottos of Arthur Machen, where natural beauty and child-like play have a dark and sinister side. Watchdogs of the Wambarrows is a true noise piece, bowed on goblets and vases along with chimes, synths and tape-loops which all get treated to create an otherworldy sound giving mind to ghostly apparitions blowing through the mist.

Taken as a whole the LP is a remarkably affecting work. I listened to it in its entirety before approaching any of the other materials of the box and, even without the background knowledge contained in the book, the LP conveys its message and theme extremely well. When combined with insights provided by the book however, the listener is moved to new heights of unease. It is a spine-tingling marvel and an audiophile’s delight. The production, performances and mixing are all flawless. Every track is an excellent technical achievement. For fans of noise, the sleeve notes give a full breakdown of the sources, instruments and equipment used on each piece.

Next we come to the DVD included within the box. It contains a single short film, entitled The Spectre Hound, on loop. It is without a doubt an art piece. Apparently made using a combination of hand-treated 16mm film and projector slides, the ten-minute film shows a collection of overlapping and layered images accompanied by an audio-montage of sound from the LP. Pictures of buildings, ruins, country lanes and gorges come in-and-out of focus, disappearing into a blur of rust, fingerprints and melting acetate. Occasionally we think we might see shapes in the visual noise – haunted faces, monstrous dogs – like some half-glimpsed apparition in the shadows at dusk. According to accompanying notes some of these effects were created by treating the film with materials gathered from the field such as ash from the fireplace of Dob Park Lodge and scorched waterweed from Troller’s Gill; imaginatively speaking, this helps tie the imagery back to these mysterious locals.

Watching it, I was put in mind of certain live musical-art performances. The Velvet Underground, in their early days when managed by Andy Warhol, would perform with cinema-projectors pointed at them from the back of the auditorium. Warhol would project several films at once onto the band as they played, tinkering with the speeds and chopping and changing reels as he liked, loosely keying it all into the music, in an attempt to create a fabulous live visual-art work. Similarly, concerts by experimental post-rock group Godspeed You! Black Emperor are accompanied by fascinating treated film-loops projected above the stage while the band themselves sit below it playing like classical musicians. Both groups (and many others) are working with multiple mediums to take their work beyond mere audio; if well-integrated these additional visual elements can heighten the art and take the spectator to new levels of aesthetic experience. I believe this is exactly the purpose of The Spectre Hound: the suggestive noise from the LP combined with the Rorschach-like visual imagery combine very effectively to create an unsettled and uncertain mood.

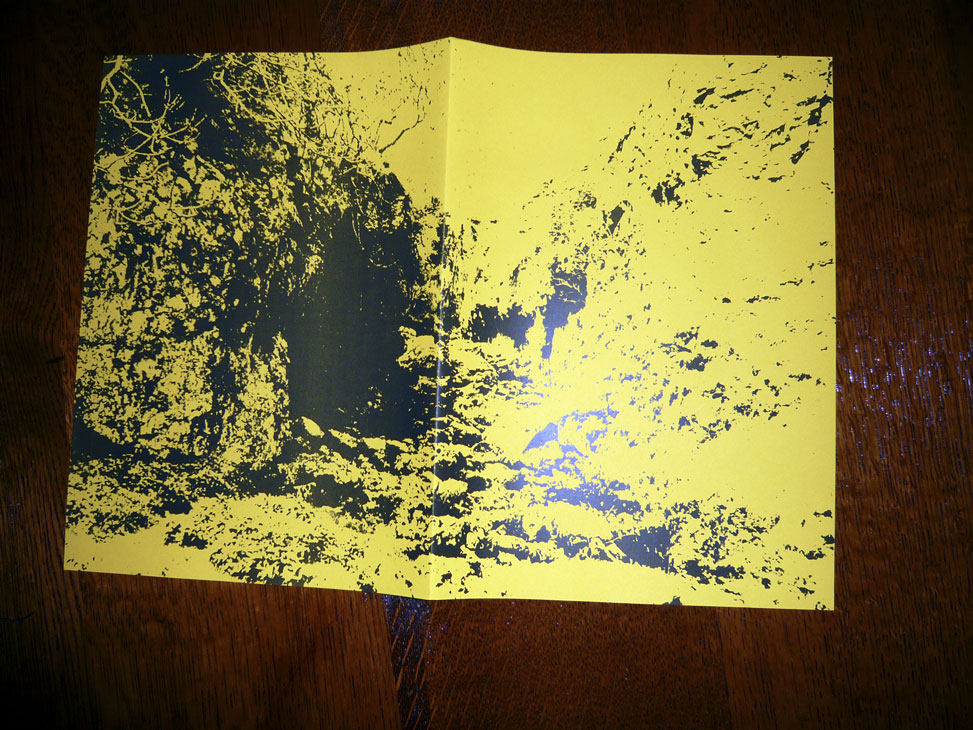

Also included in the box are two A3 Risograph prints on yellow paper, each folded in half to A4 to fit into the box. Each image appears almost as a photographic negative, stark black on bright yellow. The pictures are of locations both featured throughout the project: Dob Park Lodge, a ruined Tudor hunting lodge, and Troller’s Gill, a remote and desolate river gorge. The Lodge is photographed from across an open field, with a treeline and rolling hills behind it. Coloured as it is, that dark continuous line of black – the lodge and trees blending together – is threatening; the idea that one might have to cross that wide open field – the broad stretch of yellow paper on the page – is quite disconcerting: it feels too open and exposed; looking at the image, the eye almost fears to cross it. The Troller’s Gill print inverts this. At the image’s heart is the opening to a cave, appearing on the print an enormous black hole. The viewer’s gaze tries to shy away from it, somehow dreading to look into its stygian depths, and instead looks at the detail surrounding the dark blot. However every crack and crevice and weed – fine black lines against the bare yellow paper – seems to lead you back that terrible opening. Very simple prints, they are yet surprisingly potent.

I was, I admit, initially surprised to hear that the box contained Risograph prints. Readers may be forgiven for any unfamiliarity with Risographs, because they are not conventionally associated with quality and collectable art: Risograph is a brand of high-volume high-speed photocopiers usually used for running off cheap flyers. Strangely enough though, this seems entirely in-keeping with the feel of all of Folklore Tapes’ projects: in spite of the fact that all of their releases have had limited runs and have been hand-assembled, they all have a slightly mass-produced feel – not the slick high-volume production of today, but a cheap look that came with the industrial processes necessary for mass-production in decades past. I was put in mind of the flyers produced for illegal raves in the ‘90s – or of church service-order booklets folded and assembled by hand by volunteers but still printed, even today, on a donated old battered old photocopier in the back of the vestry. Each are peculiarly English – and that fits aesthetically, because so are these Black Dog traditions and so is this project. This is worth highlighting to potential purchasers – especially in North America where Cadabra Records (whose pictures tend to be hand-printed on silk-screen or high-gauge art paper) have distributed Folklore Tapes. The latter’s approach is unconventional, but it fits.

You can see evidence of this ethos elsewhere in the project. On the LP some of the peculiar sounds are somehow reminiscent of the old BBC Radiophonic Workshop that created the original Doctor Who theme. The photos, contained in the book, have a slight grain and soft-focus associated I associate with 1980s tourist guidebooks. Additionally, the pages in my copy of the book are printed slightly off of a perfectly straight orientation – putting me in mind of the mass-printed National Trust leaflets that used to be assembled by hand by dedicated volunteers back in the days before they received significant Government funding. This ethos also speaks to the reality of library research in general and, I imagine, folklore research in particular: there are endless photocopies to be made from books on creaking old behemoths like Risographs, inevitably producing smudged and uneven prints; one has to warm up ancient technology like those dusty and badly-maintained microfilm readers in order to view academic articles so obscure and rarely accessed that the library shrunk them to save space; then one tracks down a chapter in some side-lined and long-forgotten book – looking at the card on the inside cover, printed on a type-writer, you find that it was last taken out of the library back in the 1950s. I imagine this sort of experience informed Folklore Tapes when they began developing the style of their projects.

Summing up – the contents of this boxed-set are remarkable. Every aspect of it seems to have been thought through, and they tie together intellectually, artistically and emotionally on multiple levels. I have been incredibly impressed with the thoroughness and degree of rigour that has evidently gone into it. I suspect that this has been a real labour of love by Ian and David and I applaud them for their efforts and their results.

I can perhaps offer no higher compliment than to comment that: I myself am a rational observer of a mechanistic universe; a scientist; an historian; an student of the development of human society. With regards to phenomena we might call supernatural I am a sceptic at best. Yet Black Dog Traditions of England managed to scare me. It revived my childhood unease of the unknown. From the comfort of my living room, in a busy city and on a summer’s day – I found myself thinking about the next time I might return to my family home on Dartmoor. When I next walk the miles of country lanes at dusk to the local pub I suspect I may look differently at the lengthening shadows. I will hurry through the hedgerows, for I fear may what lurk beyond.